The city was covered with snow. The breath of cold was frozen on the bare tree trunks. A mother walked barefoot through the snow, confused and shocked. It was freezing cold. She scratched her face with one hand and held a piece of paper in the other. She screamed:

„Folks, I’m not crazy. Help! Someone should have mercy on me. This government of darkness has torn my daughter, my soul from me. This government of torture and execution executed my daughter.“

The girl Fereshteh was born in the city of Saqqez in the year 02.09.1333 Iranian Calendar (23.11.1954). She was the first child of the family. Her face was so pretty and her eyes were all dark; they looked like grapes. She had a delicate face and looked like an angel. Her appearance made it very easy to name her. My father called her Fereshteh and that means angel. The birth of this daughter was the most beautiful moment in my father’s life. Later, when she was a little older, my father used to call her Grape, that was her nickname. She spent her childhood very well looked after and loved by her mother and with the support of a generous and caring father.

Even as a child she was very creative and intelligent. The people around us who knew her remember Fereshteh as follows: “she was very helpful as a student towards the other girls who were not allowed to attend school during this time. Due to my father’s decision, she was allowed to attend school. Every day after returning from school, she would meet with the neighborhood girls and share what she had learned in school. So she was very creative and loving and passed on what other girls couldn’t learn because they weren’t allowed to attend school”.

Fereshteh’s behavior was an encouragement and motivation for the families who did not allow their daughters to attend school. Her behavior was really great and my father was very proud that his daughter was supporting the girls in the neighborhood. My father was also very proud that his daughter had the opportunity to attend school and to grow up in complete freedom despite a patriarchal society.

The feeling of human responsibility for others became part of Fereshteh’s life from childhood on. Instead of playing games, she worked hard to meet the expectations and needs of girls her age and women in the neighborhood, from learning to read and write to teaching crafts. Fereshteh had learned to be a teacher from childhood on. This particular ability to teach made her a creative, encouraging, and unique teacher. After graduating from Teacher Training University in 1350 (1971), she was engaged in education and worked as a teacher in the villages of the Saqqez area. Teaching in the villages of Kurdistan made her even stronger. Fereshteh’s seriousness in teaching, her kindness and humanity and of course her enthusiasm had created a deep bond between her and her students. The result of one teacher’s tireless efforts has resulted in her teaching today’s university professors, doctors, and nurses to serve their communities. They regretted the absence of their compassionate teacher, but kept her alive in their minds and hearts for eternity. Her name is unforgettable to them.

She did her job beyond her responsibilities. As well as being a compassionate teacher, she was a kind companion to the villagers, especially women and girls. They accepted Fereshteh as a member of their family and counseled and sympathized with her.

In addition to classes and social activities, books and reading were a large part of Fereshteh’s life. I remember my sister reading Saedi books or other writers to my mother and my mother was always waiting to hear the rest of the story.

She was then accepted in 1355 (1976) at Sanandaj College (now Kurdistan University) for a bachelor’s degree in literature. In addition to her training in Sanandaj, she also taught in Saqqez. Her political thoughts were shaped during these years and started a new chapter in her life. She was a free-thinking person and avoided rules and clichés as much as she could. She never limited her personal thoughts to one stream of thoughts. She had great respect for people’s right of freedom and did not tolerate prejudice or dogmatic thinking. She had great enthusiasm for arts and beauty and avoided commenting on it without reading or researching.

During her studies, Fereshteh was transferred to Saqqez because of her persistence and excellent teaching performance and repeated encouragement in schools. This was an opportunity to open a bookstore with a group of friends in order to offer, among other things, the “White-Cover-Books”, which were then forbidden and popular with politically active people. Our house, which housed our large family, was full of books and mostly there were friends who would sit to read wherever there was an empty space.

In July 1979, after the regime’s military invasion of Kurdistan and the start of clashes, persecution, torture and execution of the nation’s politicians and the pressure on their families, Fereshteh was forced to leave Saqqez.

Her absence in the house, the deprivation of the liveliness and warmth of her presence on the one hand and the existence of the executioners of the regime, who shamelessly and suddenly in the middle of the night climbing over the courtyard door and the house wall like looters, entering the house with muddy boots, the mattress brutally taking away from among us, on the other hand it had become one of the bitterest parts of life.

The city of Bukan, just a few kilometers from Saqqez, was still in the hands of the Kurds at that time due to the lack of a military base. This had become a free port for all political and cultural currents in Iran. Fereshteh fled to Bukan because she had been identified. She had joined the Peykar organization. The economic blockade of Kurdistan required the formation of a team of trained medical and cultural staff. This time Fereshteh went again to this safe place in the heart of the mountains, where the paradise of Kurdistan was and his friendly people lived in the villages around Bukan. At that time, when Kurdistan was under economic and logistical siege, relief teams rushed to the aid of the Kurdish people and were able to temporarily meet the medical needs of the people.

In December 1979, my father and I went to Bukan to meet with Fereshteh again. There was no vehicle and in this cold winter we had to walk from Bukan to the village where they lived. When I saw Fereshteh in this male Kurdish dress with her beautiful smile and her friends, all of whom were full of passion for life, all my nostalgia and fear turned into joy and peace. That was the last time Fereshteh‘s beautiful sisterly hands caressed me.

She was dismissed from teaching in 1980 by the regime. In the same year Fereshteh married Sarem Eftekhari. They were transferred to Sanandaj through their Organization Peykar to continue their political activities. In the dark and terrible heart of those days in Sanandaj, they secretly began propaganda work.

At that point, panic had become a part of my father’s life. My father used to say: “I don’t hear from her at all. I fear that she is in danger. This shows the irresponsibility and irrationality of those who are responsible. I fear that this lack of seriousness will lead to them being exposed and arrested.”

And so it happened. They were known to the regime and unfortunately both were arrested in Sanandaj. By the time they were arrested, they had already resigned from the Peykar Organization. Shortly after leaving, the Peykar Organization disbanded due to the betrayal of its leaders. The only reason Fereshteh and Sarem stayed in Sanandaj was because of their sense of responsibility and their humane nature. Despite the ability to get out of town quickly, they knew it was their duty to keep supporters and those who worked with the movement informed. They didn’t want to leave the battlefield just to save themselves. Undoubtedly, their sense of responsibility towards their comrades and their humane character were outstanding features of the two.

Government agents knew about Sarem’s activities; they knew that Fereshteh was his wife, but they had no idea of her responsibilities and activities. The person who arrested and identified the two was a person named (R.Kh.). (1)

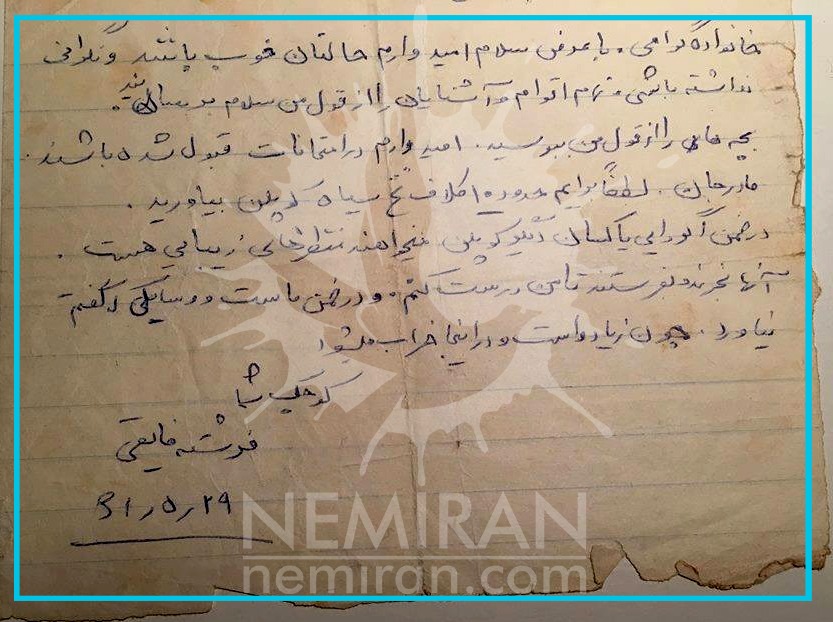

When we got the news of her detension through her little secret letter from prison, Sarem at first had no information about Fereshteh’s arrest and his only wish before his execution was that Fereshteh should stay alive. In this letter, Fereshteh asked my mother to vacate her and Sarem’s property and belongings immediately and to move them to a safe place. Unfortunately, all confiscated property and the house have been completely cleared by the government. It was not easy for my parents to go from prison to prison in a city where every corner had been turned into a prison. My father cried and said, “I wish I knew who was responsible for putting Fereshteh and Sarem in this life-threatening position in Sanandaj?”

The regime recognized Sarem as one of the leaders of the organization and for this reason he was subjected to the most severe tortures from the moment of his arrest. All of the regime’s efforts were aimed at bringing Sarem to his knees. A witness who was in prison with Sarem recalls: “In order to force Sarem to repent and confess on television, the famous Mullah Mesbah Yazdi was brought to Sanandaj to discuss ideology with Sarem. After the discussion, he said that Sarem Eftekhari could turn him into an unbeliever rather than convert Sarem to Islam.”

The government subjected him to the most severe physical and mental torture and executed him. They were even afraid of his mutilated body. They only half buried the body in the desert near the city of Qorveh, far away from his family. He was wrapped in a white cloth with his name written on it. A shepherd found him near his farm and removed his name from his neck and buried the body.

But Fereshteh stayed in prison. She was initially able to introduce herself with a different identity and pretend she was just the wife of Sarem with no political activities against the government. During this time she played an important role in maintaining prisoners’ morale in the public prison and as always came to help other prisoners. Everyone was enthusiastic about her warm and friendly personality, her serenity and her respectful behavior.

During one of the interrogations, Fereshteh was shown a picture of a Peykar comrade, and Fereshteh said she never saw or knew her. During their first personal meeting Fereshteh put a small letter in my mother’s mouth when she hugged and kissed her. In the above letter, she asked that my mother find some way to find the woman and inform her so that she would not be arrested and her life would not be in danger. My mother and sister found the young woman and informed her about the incident. Fereshteh had found creative ways to correspond with us one-way, and this time she had benefited from the manual skills of her childhood. She wrote a small letter on a paper napkin, piped it and embedded it in knitwear and small works of art. She had done her job with full care. We searched her belongings very carefully every time my mother brought things from prison. Whenever there was a letter, we kissed it and wrote it again. Sometimes Fereshteh wrote us letters in an ugly handwriting and in a particularly simple style of writing so that she presented herself as a normal, apolitical woman. The letter was not intended to reveal her true identity if discovered.

Personal visits to the prison were gradually banned and meetings were held at a distance and behind bars. During one of the meetings when my little sister was accompanying my mother, she noticed that Fereshteh could barely hold her chador (Islamic female body dressing). Part of the bandaged hand could be seen under the chador. This time, when my mother received the finished knitted piece from Fereshteh, we opened the knitted collar, took out the letter and the contents was much longer than in the previous letters. That confused and surprised us all.

Fereshteh mentioned in the letter that she had been subjected to the most severe torture and long interrogation for a long time, and that two interrogators questioned her. Fereshteh mentioned a woman by the name of G. Sh., a collaborator in Sanandaj Prison, as the main interrogator. She wrote: “Her kicks hurt me more mentally than physically. She asked me to testify against Sarem, forced me to confess publicly on television and urged me to repent so as not to be executed. ”She continued: “G.Sh. testified wrongly and exaggerated about Sarem and me than we actually had done. Be prepared for the fact that if she makes a public confession on television I’ll be executed soon. “

We rewrote this letter and my father handed it over to Komala Organization. Since we had already sent Fereshteh’s previous letters, the contents of these letters reflected the prison situation. As much as possible, this had become part of her political work in prison. In her last letter she wrote: “I hid my last will in one of the knitwears. You will receive my letter when my personal belongings will be handed over to you.”

Fereshteh was hanged like a hero on December 9th, 1361 Iranian Calendar (February 28th, 1983) in the middle of a cold and dark night with an injured body.

The news of Fereshteh’s execution awoke the city of Saqqez. The house, the yard and the alleys were full of crying people. But our house was besieged in no time and threatened with silence, and we were not allowed to hold a funeral service. On January 12th, 1362 (April 1st, 1983) my parents went to Kermanshah. My mother wanted to dig up the ground with her bare hands and kept moaning and moaning. Meanwhile, the person in charge of the funeral of the executed came to my mother and said, “Calm down mother, I want to say something. Pray that I will go on living to eventually explain to people what happened to the best and most precious treasures of this land. Your daughter was the most heroic person I have ever known. She went to her execution with a smile in her face and her head held high. Know that even her silent body was full of screams. I wrapped her respectfully like a hero in a white sheet, not a plastic bag, and buried her with pride, so that her tired and tortured body could find its final rest. Oh mother, pray that I will stay alive so I can reveal the message of her last smile to the ignorant. One day I will dig up her grave, hidden from the eyes of the executioners, so you can see the last scream in her eyes.”

After the execution of Fereshteh, G.Sh. (2) visited together with a Zainab-Sisters-Team (the women’s organization of the Revolutionary Guard) a high school in Saqqez to give a speech. Our little sister was a student there. My sister had seen G.Sh. on TV, the name was well known to her because it was connected with the execution of Fereschteh. My sister told her teacher that she had a bad stomachache and had to go home. My sister used to tell, when she saw G.Sh. she almost vomited. When my sister came back from school and my mother found out about it, she rushed to school and attacked G.Sh. in front of the school entrance. She asked her:”What was my daughter’s last message and what was in her last will?” G.Sh. kicked my mother and, with the help of her companion, threw my mother aside. She replied that Fereschteh herself was responsible for resisting until the last breath and not giving up.

Author:

Pari Fayqi, Fereschteh’s sister

Note:

The names of the persons named under (1) and (2) will be reserved by the Nemiran website until an appropriate time.